www.bustedstreightboys.com

The time is flying as a bird and i'm not saying any word!

вторник, 29 января 2013 г.

Привет дорогой Гена!

Просмотрел сегодня на фейсбуке странички Ромы, Наташи и некоторых

наших общих знакомых. Узнал для себя много интересного!

Кстати, я заходил к Олегу Дальницкому на работу, в его новый офис по

Михай Витязу 17.

Олег Георгиевич мне немного помог деньгами и рекомендовал мне браться

за ум, работать и зарабатывать деньги. Становиться деловым человеком и бизнесмэном, как раньше.

Даже обсуждали возможность моей работы у него.

Я раньше обслуживал две их структуры: Irida & UBFB. http://irida.md/

http://ubfb.md/

Знаю гл. буха Олега - Лену, а также его компаньонов Сашу и Игоря.

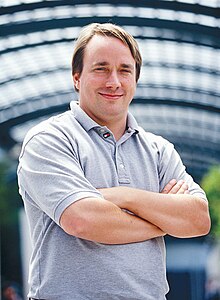

Здесь прилагается фотография Олега и Дениса Дальницких. Они довольно похожи.

Был так же у Серёжи Швеца на ул.Фередеулуй 4, в его типографии.

http://www.monarch.md/

Он мне дал 50 лей и предложил у него работать менеджером по

продвижению его продукции. На проценты от заключённый мной контрактов.

Но пока что я непонятно где живу, хожу как бомж, бич и оборванец,

половины зубов нет.

Сегодня вот троллейбус, в котором я ехал, столкнулся с автобусом 28

маршрута примерно в 12-00 на ул.Григоре Виеру.

Много человек пострадало. Я едва удержался на ногах.

Какие у меня будут заключены контракты на изготовление печатной

продукции, этикеток и упаковки с такими вот моими внешними данными и

бытовыми условиями проживания?

Я звонил Жоре Гуцу, но как я понял он до Нового Года куда-то уехал и

до сих пор так и не появился в Кишинёве.

Поэтому, поскольку я не работаю пока, то живу, как могу, на пенсию в

480 лей в месяц.

Такие вот мои дела.

http://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.472156629487539.96501.103829132986959&type=1

http://www.facebook.com/ritaabashkina

http://www.facebook.com/daniela.guma.3

http://www.facebook.com/Mexx

http://www.facebook.com/natalia.abaschina?fref=ts

http://www.facebook.com/inbox.arg/friends?ft_ref=frh

http://www.facebook.com/denis.dalinitsky

и много-много других очень интересных.

У меня есть возможность сравнить меня, нищего бомжа, с нормальными

здоровыми, сытыми, полноценными людьми.

И сделать выводы.

Наталья И Геннадий! Давайте помиримся и снова будем дружить семьями как раньше!

Автор:

Славик Богачёв

Просмотрел сегодня на фейсбуке странички Ромы, Наташи и некоторых

наших общих знакомых. Узнал для себя много интересного!

Кстати, я заходил к Олегу Дальницкому на работу, в его новый офис по

Михай Витязу 17.

Олег Георгиевич мне немного помог деньгами и рекомендовал мне браться

за ум, работать и зарабатывать деньги. Становиться деловым человеком и бизнесмэном, как раньше.

Даже обсуждали возможность моей работы у него.

Я раньше обслуживал две их структуры: Irida & UBFB. http://irida.md/

http://ubfb.md/

Знаю гл. буха Олега - Лену, а также его компаньонов Сашу и Игоря.

Здесь прилагается фотография Олега и Дениса Дальницких. Они довольно похожи.

Был так же у Серёжи Швеца на ул.Фередеулуй 4, в его типографии.

http://www.monarch.md/

Он мне дал 50 лей и предложил у него работать менеджером по

продвижению его продукции. На проценты от заключённый мной контрактов.

Но пока что я непонятно где живу, хожу как бомж, бич и оборванец,

половины зубов нет.

Сегодня вот троллейбус, в котором я ехал, столкнулся с автобусом 28

маршрута примерно в 12-00 на ул.Григоре Виеру.

Много человек пострадало. Я едва удержался на ногах.

Какие у меня будут заключены контракты на изготовление печатной

продукции, этикеток и упаковки с такими вот моими внешними данными и

бытовыми условиями проживания?

Я звонил Жоре Гуцу, но как я понял он до Нового Года куда-то уехал и

до сих пор так и не появился в Кишинёве.

Поэтому, поскольку я не работаю пока, то живу, как могу, на пенсию в

480 лей в месяц.

Такие вот мои дела.

http://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.472156629487539.96501.103829132986959&type=1

http://www.facebook.com/ritaabashkina

http://www.facebook.com/daniela.guma.3

http://www.facebook.com/Mexx

http://www.facebook.com/natalia.abaschina?fref=ts

http://www.facebook.com/inbox.arg/friends?ft_ref=frh

http://www.facebook.com/denis.dalinitsky

и много-много других очень интересных.

У меня есть возможность сравнить меня, нищего бомжа, с нормальными

здоровыми, сытыми, полноценными людьми.

И сделать выводы.

Наталья И Геннадий! Давайте помиримся и снова будем дружить семьями как раньше!

418112_471407222907018_713425977_n.jpg57 Kb

понедельник, 28 января 2013 г.

Федя Еланцев 29 лет, Сынжерей, Молдова

Military - weapons.

|

|

| ||||||

|

|

| ||||||

|

|

|

воскресенье, 27 января 2013 г.

…Numele Ghenadi Abaşkin apare totuşi şi în alte ipostaze, împrejurările fiind dintre cele mai surprinzătoare.

Важное!

Scrisoare deschisă către Înalt Preasfinţia Sa Mitropolitul Chişinăului şi al Întregii Moldove Vladimir

Nume cunoscute în contexte extrem de periculoase...

http://www.timpul.md/articol/

R. Moldova este prea mică pentru ca în ea să poată exista mistere. Şi

totuşi, lumea insistă în mister, îşi acoperă faţa, îşi desenează

cărările mai mult prin întuneric, ascunde adevăratele plăceri,

adevăratele vocaţii.

Constatările de mai sus pot fi argumentate printr-o diversitate de exemple, însă unul dintre acestea pare să fie totuşi mai relevant.

De la un timp, tot mai frecvent iese la suprafaţă un nume în dreptul căruia până nu demult eram obişnuiţi să citim o singură calitate - reprezentantul Concernului „Gazprom” în R. Moldova. Da, într-adevăr, este vorba despre acel Ghenadi Abaşkin, nume după care, spre surprinderea multora, astăzi apar calificative dintre cele mai neverosimile. Bunăoară, relativ nu demult, presa de la Chişinău a multiplicat o ştire greu de crezut - Ghenadi Abaşkin a devenit cetăţean al Transnistriei. Şi asta în pofida faptului că acelaşi Ghenadi Abaşkin reprezintă „Gazprom”-ul rusesc în Republica Moldova - ţară care, ca şi Federaţia Rusă, nu recunoaşte o asemenea cetăţenie. Ştirea nu a fost dezminţită sau contestată în niciun fel. Probabil şi din motiv că este destul de greu să conteşti un ukaz al lui Smirnov prin care oficialului respectiv i se conferă cetăţenie la Tiraspol.

…Numele Ghenadi Abaşkin apare totuşi şi în alte ipostaze, împrejurările fiind dintre cele mai surprinzătoare. Iată ce ne este dat să citim pe httm://bogaciov.blogspot.com/

Totul ar ţine de domeniul firescului: cineva, pe nume Vladislav Bogaciov, nume strâns legat de mişcarea sectantă Pangu-Purusha, îi mulţumeşte lui Ghenadi Abaşkin pentru că acesta există. Şi chiar se roagă de sănătatea lui, de binele lui, de prosperare. Dar lucrurile nu sunt chiar atât de simple, există şi unele „detalii”: „În anul 2006, demonii m-au informat că escortarea gay-ilor nu mai este actuală şi că eu trebuie să fac lucruri mult mai serioase: să scot din scumpul şi unicul meu văr Ghenadi Aleksandrovici Abaşkin (Ghena Abaşkin) 200.000 de euro”. Caracterul financiar al implicării eroului nostru în activităţi mai puţin normale pentru o societate ne obligă să tragem clopotele. Şi ne mai cere să întrebăm dacă există vreo legătură între numele reprezentantului concernului rus şi traficul de fiinţe sexual deviate. Dacă acest trafic are cumva ca destinaţie R. Moldova sau doar R. Moldova. Dacă aceşti bani - 200.000 de euro sunt singurii care dau atingere proiectelor derulate de acest Bogaciov. Însuşi contextul în care apare numele Abaşkin este unul extrem de periculos pentru societate. Pentru orice societate. Acordarea de sprijin unor secte fără acte pe teritoriul R. Moldova înseamnă a te afla în relaţii de confruntare cu legislaţia. Înseamnă a stimula nişte procese care iau amploare nu doar în Moldova, dar şi în ţările din regiune. Mai ales atunci când este vorba despre anumite curente sataniste. Acestea duc aproape fără nicio excepţie la creşterea alarmantă a actelor de violenţă, omuciderilor, sinuciderilor şi orgiilor de tot felul. Cum majoritatea grupărilor sataniste desfăşoară o activitate conspirativă, e greu de precizat în momentul de faţă care este numărul sataniştilor în general şi numărul lor în Moldova în particular. Ceea ce se ştie cu certitudine e că adepţii sunt recrutaţi, în marea lor majoritate, din rândurile tinerilor, elevi şi studenţi având vârste cuprinse între 12 şi 25 de ani. Modalităţile de atragere sunt diferite, dar aproape toate aceste modalităţi au ca instrument de lucru banul. Poate din acest considerent ar fi fost nevoie de 200.000 de euro?

Aşa cum am spus iniţial, Moldova este prea mică pentru ca să putem avea mistere. Dar tot această Moldovă este suficient de mare pentru a da impuls unor fenomene devastatoare. Iată de ce suntem obligaţi să recitim cu destulă atenţie nişte texte ajunse cu multă, multă uşurinţă sub privirile noastre, să subliniem numele care apar printre cuvinte şi să formulăm clar întrebările.

Constatările de mai sus pot fi argumentate printr-o diversitate de exemple, însă unul dintre acestea pare să fie totuşi mai relevant.

De la un timp, tot mai frecvent iese la suprafaţă un nume în dreptul căruia până nu demult eram obişnuiţi să citim o singură calitate - reprezentantul Concernului „Gazprom” în R. Moldova. Da, într-adevăr, este vorba despre acel Ghenadi Abaşkin, nume după care, spre surprinderea multora, astăzi apar calificative dintre cele mai neverosimile. Bunăoară, relativ nu demult, presa de la Chişinău a multiplicat o ştire greu de crezut - Ghenadi Abaşkin a devenit cetăţean al Transnistriei. Şi asta în pofida faptului că acelaşi Ghenadi Abaşkin reprezintă „Gazprom”-ul rusesc în Republica Moldova - ţară care, ca şi Federaţia Rusă, nu recunoaşte o asemenea cetăţenie. Ştirea nu a fost dezminţită sau contestată în niciun fel. Probabil şi din motiv că este destul de greu să conteşti un ukaz al lui Smirnov prin care oficialului respectiv i se conferă cetăţenie la Tiraspol.

…Numele Ghenadi Abaşkin apare totuşi şi în alte ipostaze, împrejurările fiind dintre cele mai surprinzătoare. Iată ce ne este dat să citim pe httm://bogaciov.blogspot.com/

Totul ar ţine de domeniul firescului: cineva, pe nume Vladislav Bogaciov, nume strâns legat de mişcarea sectantă Pangu-Purusha, îi mulţumeşte lui Ghenadi Abaşkin pentru că acesta există. Şi chiar se roagă de sănătatea lui, de binele lui, de prosperare. Dar lucrurile nu sunt chiar atât de simple, există şi unele „detalii”: „În anul 2006, demonii m-au informat că escortarea gay-ilor nu mai este actuală şi că eu trebuie să fac lucruri mult mai serioase: să scot din scumpul şi unicul meu văr Ghenadi Aleksandrovici Abaşkin (Ghena Abaşkin) 200.000 de euro”. Caracterul financiar al implicării eroului nostru în activităţi mai puţin normale pentru o societate ne obligă să tragem clopotele. Şi ne mai cere să întrebăm dacă există vreo legătură între numele reprezentantului concernului rus şi traficul de fiinţe sexual deviate. Dacă acest trafic are cumva ca destinaţie R. Moldova sau doar R. Moldova. Dacă aceşti bani - 200.000 de euro sunt singurii care dau atingere proiectelor derulate de acest Bogaciov. Însuşi contextul în care apare numele Abaşkin este unul extrem de periculos pentru societate. Pentru orice societate. Acordarea de sprijin unor secte fără acte pe teritoriul R. Moldova înseamnă a te afla în relaţii de confruntare cu legislaţia. Înseamnă a stimula nişte procese care iau amploare nu doar în Moldova, dar şi în ţările din regiune. Mai ales atunci când este vorba despre anumite curente sataniste. Acestea duc aproape fără nicio excepţie la creşterea alarmantă a actelor de violenţă, omuciderilor, sinuciderilor şi orgiilor de tot felul. Cum majoritatea grupărilor sataniste desfăşoară o activitate conspirativă, e greu de precizat în momentul de faţă care este numărul sataniştilor în general şi numărul lor în Moldova în particular. Ceea ce se ştie cu certitudine e că adepţii sunt recrutaţi, în marea lor majoritate, din rândurile tinerilor, elevi şi studenţi având vârste cuprinse între 12 şi 25 de ani. Modalităţile de atragere sunt diferite, dar aproape toate aceste modalităţi au ca instrument de lucru banul. Poate din acest considerent ar fi fost nevoie de 200.000 de euro?

Aşa cum am spus iniţial, Moldova este prea mică pentru ca să putem avea mistere. Dar tot această Moldovă este suficient de mare pentru a da impuls unor fenomene devastatoare. Iată de ce suntem obligaţi să recitim cu destulă atenţie nişte texte ajunse cu multă, multă uşurinţă sub privirile noastre, să subliniem numele care apar printre cuvinte şi să formulăm clar întrebările.

Un articol de: Adrian Baltag

Copyright © 2011 Reproducerea totală sau parţială a materialelor

necesită acordul în scris al Publicaţiei Periodice TIMPUL DE DIMINEAŢĂ

E o situaţie pe care ar putea s-o clarifice doar ÎPS Vladimir…

Scrisoare deschisă către Înalt Preasfinţia Sa Mitropolitul Chişinăului şi al Întregii Moldove Vladimir

Noi, un grup de enoriaşi ai bisericilor din Chişinău, luminaţi de

credinţa în Bunul Dumnezeu, ne vedem obligaţi să ne adresăm către Înalt

Preasfinţia Sa Mitropolitul Chişinăului şi al Întregii Moldove Vladimir

pentru a face lumină asupra unor situaţii peste care nu putem trece cu

nepăsare. Aşa cum am fost călăuziţi să înţelegem, ştim bine că

Mitropolia este, în cele din urmă, responsabilă pentru condiţia morală

şi spirituală a noastră, tot ea având şi obligaţiunea de a-şi expune

clar poziţia asupra tuturor încercărilor de intimidare, de defăimare, de

rătăcire şi atragere a cetăţenilor în diverse mişcări şi întruniri

străine Bisericii ortodoxe. Noi nu întârziem să ne implicăm la modul

personal în diferite asemenea cazuri, însă există situaţii care depăşesc

puterea pe care o avem… Şi anume. Am citit nu demult în presă un

articol în care se spune că, alături de alte secte care nu aduc decât

dezbinare în rândul oamenilor şi care doresc să domine asupra unor

mulţimi amăgite şi atrase în capcane, în RM e pe cale de a-şi extinde

ramificaţiile o altă grupare pretins religioasă, numită Pangu-Purusha.

Evităm să scriem aici numele celui care se autodefineşte drept cap al

acestei secte, din simplul motiv că nu toate câte se spun merită să fie

tirajate, dar mai ales date drept subiect de interes general.

Ceea ce nu poate să nu trezească nedumerirea şi indignarea noastră este că în articolul „Nume cunoscute în contexte extrem de periculoase”, publicat în cotidianul TIMPUL, alături de animatorii sectei respective apare numele lui Ghennadi Abaşkin. Calitatea noastră de simpli cetăţeni nu ne permite să clarificăm despre care Abaşkin este vorba, însă anumite referinţe alăturate acestuia ne fac să bănuim că ar putea fi vorba despre actualul reprezentant în RM al Concernului rus „Gazprom”. Ca dovadă se poate reciti următorul fragment: „V. B., nume strâns legat de mişcarea sectantă Pangu-Purusha, îi mulţumeşte lui Ghennadi Abaşkin pentru că acesta există. Şi chiar se roagă de sănătatea lui, de binele lui, de prosperare”. Dar lucrurile nu sunt chiar atât de simple, există şi unele „detalii”: „În anul 2006, demonii m-au informat că escortarea gay-ilor nu mai este actuală şi că eu trebuie să fac lucruri mult mai serioase: să scot din scumpul şi unicul meu văr Ghennadi Aleksandrovici Abaşkin (Ghena Abaşkin) 200.000 de euro”. (…)

Sprijinirea unor secte fără acte pe teritoriul RM înseamnă a te afla în relaţii de confruntare cu legislaţia. Înseamnă a stimula nişte procese ce iau amploare nu doar în RM, ci şi în ţările din regiune. Mai ales atunci când e vorba de anumite curente sataniste. Acestea duc aproape fără nicio excepţie la creşterea alarmantă a actelor de violenţă, omuciderilor, sinuciderilor şi orgiilor. Cum majoritatea grupărilor sataniste desfăşoară o activitate conspirativă, e greu de precizat, în momentul de faţă, care e numărul sataniştilor în general şi numărul lor în Moldova în particular.

După apariţia articolului citat, am urmărit cu atenţie presa din RM, dar nu am văzut ca Ghennadi Abaşkin să infirme undeva informaţiile cu pricina. Această tăcere ne îngrijorează, obligându-ne să facem apel la Înalt Preasfinţia Voastră cu rugămintea fie de a limpezi lucrurile, fie de a interveni, cu puterea pe care o aveţi, pentru a nu lăsa ca societatea să cadă pradă sataniştilor, pentru a curma faptele de finanţare a acestor activităţi, pentru a sesiza Biserica Rusă, ca aceasta din urmă să facă lumină peste cugetul şi faptele cetăţeanului Federaţiei Ruse, Ghennadi Abaşkin.

Vasile Zaiaţ, în numele unui grup de veterani de război

Ceea ce nu poate să nu trezească nedumerirea şi indignarea noastră este că în articolul „Nume cunoscute în contexte extrem de periculoase”, publicat în cotidianul TIMPUL, alături de animatorii sectei respective apare numele lui Ghennadi Abaşkin. Calitatea noastră de simpli cetăţeni nu ne permite să clarificăm despre care Abaşkin este vorba, însă anumite referinţe alăturate acestuia ne fac să bănuim că ar putea fi vorba despre actualul reprezentant în RM al Concernului rus „Gazprom”. Ca dovadă se poate reciti următorul fragment: „V. B., nume strâns legat de mişcarea sectantă Pangu-Purusha, îi mulţumeşte lui Ghennadi Abaşkin pentru că acesta există. Şi chiar se roagă de sănătatea lui, de binele lui, de prosperare”. Dar lucrurile nu sunt chiar atât de simple, există şi unele „detalii”: „În anul 2006, demonii m-au informat că escortarea gay-ilor nu mai este actuală şi că eu trebuie să fac lucruri mult mai serioase: să scot din scumpul şi unicul meu văr Ghennadi Aleksandrovici Abaşkin (Ghena Abaşkin) 200.000 de euro”. (…)

Sprijinirea unor secte fără acte pe teritoriul RM înseamnă a te afla în relaţii de confruntare cu legislaţia. Înseamnă a stimula nişte procese ce iau amploare nu doar în RM, ci şi în ţările din regiune. Mai ales atunci când e vorba de anumite curente sataniste. Acestea duc aproape fără nicio excepţie la creşterea alarmantă a actelor de violenţă, omuciderilor, sinuciderilor şi orgiilor. Cum majoritatea grupărilor sataniste desfăşoară o activitate conspirativă, e greu de precizat, în momentul de faţă, care e numărul sataniştilor în general şi numărul lor în Moldova în particular.

După apariţia articolului citat, am urmărit cu atenţie presa din RM, dar nu am văzut ca Ghennadi Abaşkin să infirme undeva informaţiile cu pricina. Această tăcere ne îngrijorează, obligându-ne să facem apel la Înalt Preasfinţia Voastră cu rugămintea fie de a limpezi lucrurile, fie de a interveni, cu puterea pe care o aveţi, pentru a nu lăsa ca societatea să cadă pradă sataniştilor, pentru a curma faptele de finanţare a acestor activităţi, pentru a sesiza Biserica Rusă, ca aceasta din urmă să facă lumină peste cugetul şi faptele cetăţeanului Federaţiei Ruse, Ghennadi Abaşkin.

Vasile Zaiaţ, în numele unui grup de veterani de război

Un articol de: Opinia Cititorului

- Etichete:

- îps vladimir,

- secte,

- ghennadi abaşkin

Copyright © 2011 Reproducerea totală sau parţială a materialelor

necesită acordul în scris al Publicaţiei Periodice TIMPUL DE DIMINEAŢĂ

Hacker is a term that has been used to mean a variety of different things in computing. Про хакеров.

Мне нужна помощь! Хакер (англ. hacker, от to hack — рубить, кромсать) — чрезвычайно квалифицированный ИТ-специалист,

человек, который понимает самые глубины работы компьютерных систем.

Изначально хакерами называли программистов, которые исправляли ошибки в

программном обеспечении каким-либо быстрым и далеко не всегда элегантным

(в контексте используемых в программе стиля программирования и ее общей

структуры, дизайна интерфейсов) или профессиональным способом; слово hack

пришло из лексикона хиппи, в русском языке есть идентичное жаргонное

слово «врубаться». Сейчас хакеров очень часто отождествляют с

компьютерными взломщиками — крэкерами (англ. cracker, от to crack — раскалывать, разламывать); однако такое употребление слова «хакер» неверно.

Хакерами называют, например, Линуса Торвальдса, Ричарда Столлмана, Ларри Уолла, Дональда Кнута, Бьёрна Страуструпа, Эрика Рэймонда[источник не указан 571 день], Эндрю Таненбаума и других создателей открытых систем мирового уровня. В России ярким примером хакера является Крис Касперски.

Иногда этот термин применяют для обозначения специалистов вообще — в том контексте, что они обладают очень детальными знаниями в каких-либо вопросах или имеют достаточно нестандартное и конструктивное мышление. С момента появления этого слова в форме компьютерного термина (1960-е годы), у него появлялись новые, часто различные значения.

Хакер (изначально — кто-либо, делающий мебель при помощи топора):

В последнее время слово «хакер» имеет менее общее определение — этим термином называют всех сетевых взломщиков, создателей компьютерных вирусов и других компьютерных преступников, таких как кардеры, крэкеры, скрипт-кидди. Многие компьютерные взломщики по праву могут называться хакерами, потому как действительно соответствуют всем (или почти всем) вышеперечисленным определениям слова «хакер». Хотя в каждом отдельном случае следует понимать, в каком смысле используется слово «хакер» — в смысле «знаток» или в смысле «взломщик».

В ранних значениях, в компьютерной сфере, «хакерами» называли программистов с более низкой квалификацией, которые писали программы соединяя вместе готовые «куски» программ других программистов, что приводило к увеличению объёмов и снижению быстродействия программ. Процессоры в то время были «тихоходами» по сравнению с современными, а HDD объёмом 4,7 Гб был «крутым» для ПК. И было бы некорректно говорить о том, что «хакеры» исправляли ошибки в чужих программах.

Брюс Стерлинг в своей работе «Охота на хакеров»[2] возводит хакерское движение к движению телефонных фрикеров, которое сформировалось вокруг американского журнала TAP, изначально принадлежавшего молодёжной партии йиппи (Youth International Party), которая явно сочувствовала коммунистам. Журнал TAP представлял собою техническую программу поддержки (Technical Assistance Program) партии Эбби Хоффмана (Abbie Hoffman), помогающую неформалам бесплатно общаться по межгороду и производить политические изменения в своей стране, порой несанкционированные властями.

Персонажи-хакеры достаточно распространены в научной фантастике, особенно в жанре киберпанк. В этом контексте хакеры обычно являются протагонистами, которые борются с угнетающими структурами, которыми преимущественно являются транснациональные корпорации. Борьба обычно идёт за свободу и доступ к информации. Часто в подобной борьбе звучат коммунистические или анархические лозунги.

В России, Европе и Америке взлом компьютеров, уничтожение информации, создание и распространение компьютерных вирусов и вредоносных программ преследуется законом. Злостные взломщики согласно международным законам по борьбе с киберпреступностью подлежат экстрадиции подобно военным преступникам.

Первоначально появилось жаргонное слово «to hack» (рубить, кромсать). Оно означало процесс внесения изменений «на лету» в свою или чужую программу (предполагалось, что имеются исходные тексты программы). Отглагольное существительное «hack» означало результаты такого изменения. Весьма полезным и достойным делом считалось не просто сообщить автору программы об ошибке, а сразу предложить ему такой хак, который её исправляет. Слово «хакер» изначально произошло именно отсюда.

Хак, однако, не всегда имел целью исправление ошибок — он мог менять поведение программы вопреки воле её автора. Именно подобные скандальные инциденты, в основном, и становились достоянием гласности, а понимание хакерства как активной обратной связи между авторами и пользователями программ никогда журналистов не интересовало. Затем настала эпоха закрытого программного кода, исходные тексты многих программ стали недоступными, и положительная роль хакерства начала сходить на нет — огромные затраты времени на хак закрытого исходного кода могли быть оправданы только очень сильной мотивацией — такой, как желание заработать деньги или скандальную популярность.

В результате появилось новое, искажённое понимание слова «хакер»: оно означает злоумышленника, использующего обширные компьютерные знания для осуществления несанкционированных, иногда вредоносных действий в компьютере — взлом компьютеров, написание и распространение компьютерных вирусов. Впервые в этом значении слово «хакер» было употреблено Клиффордом Столлом в его книге «Яйцо кукушки», а его популяризации немало способствовал голливудский кинофильм «Хакеры». В подобном компьютерном сленге слова «хак», «хакать» обычно относятся ко взлому защиты компьютерных сетей, веб-серверов и тому подобному.

Отголоском негативного восприятия понятия «хакер» является слово «кулхацкер» (от англ. cool hacker), получившее распространение в отечественной околокомпьютерной среде практически с ростом популярности исходного слова. Этим термином обычно называют дилетанта, старающегося походить на профессионала хотя бы внешне — при помощи употребления якобы «профессиональных» хакерских терминов и жаргона, использования «типа хакерских» программ без попыток разобраться в их работе и т. п. Название «кулхацкер» иронизирует над тем, что такой человек, считая себя крутым хакером (англ. cool hacker), настолько безграмотен, что даже не может правильно прочитать по-английски то, как он себя называет. В англоязычной среде такие люди получили наименование «скрипт-кидди».

Некоторые из личностей, известных как поборники свободного и открытого программного обеспечения — например, Ричард Столлман — призывают к использованию слова «хакер» только в первоначальном смысле.

Весьма подробные объяснения термина в его первоначальном смысле приведены в статье Эрика Рэймонда «Как стать хакером»[3]. Также Эрик Рэймонд предложил в октябре 2003 года эмблему для хакерского сообщества — символ «глайдера» (glider) из игры «Жизнь». Поскольку сообщество хакеров не имеет единого центра или официальной структуры, предложенный символ нельзя считать официальным символом хакерского движения. По этим же причинам невозможно судить о распространённости этой символики среди хакеров — хотя вполне вероятно, что какая-то часть хакерского сообщества приняла её.

Today, mainstream usage of "hacker" mostly refers to computer criminals, due to the mass media usage of the word since the 1980s. This includes what hacker slang calls "script kiddies," people breaking into computers using programs written by others, with very little knowledge about the way they work. This usage has become so predominant that the general public is unaware that different meanings exist. While the self-designation of hobbyists as hackers is acknowledged by all three kinds of hackers, and the computer security hackers accept all uses of the word, people from the programmer subculture consider the computer intrusion related usage incorrect, and emphasize the difference between the two by calling security breakers "crackers" (analogous to a safecracker).

Currently, "hacker" is used in two main conflicting ways

As a result of this difference, the definition is the subject of heated controversy. The wider dominance of the pejorative connotation is resented by many who object to the term being taken from their cultural jargon and used negatively,[8] including those who have historically preferred to self-identify as hackers. Many advocate using the more recent and nuanced alternate terms when describing criminals and others who negatively take advantage of security flaws in software and hardware. Others prefer to follow common popular usage, arguing that the positive form is confusing and unlikely to become widespread in the general public. A minority still stubbornly use the term in both original senses despite the controversy, leaving context to clarify (or leave ambiguous) which meaning is intended. It is noteworthy, however, that the positive definition of hacker was widely used as the predominant form for many years before the negative definition was popularized. "Hacker" can therefore be seen as a shibboleth, identifying those who use the technically oriented sense (as opposed to the exclusively intrusion-oriented sense) as members of the computing community.

A possible middle ground position has been suggested, based on the observation that "hacking" describes a collection of skills which are used by hackers of both descriptions for differing reasons. The analogy is made to locksmithing, specifically picking locks, which — aside from its being a skill with a fairly high tropism to 'classic' hacking — is a skill which can be used for good or evil. The primary weakness of this analogy is the inclusion of script kiddies in the popular usage of "hacker", despite the lack of an underlying skill and knowledge base. Sometimes, hacker also is simply used synonymous to geek: "A true hacker is not a group person. He's a person who loves to stay up all night, he and the machine in a love-hate relationship... They're kids who tended to be brilliant but not very interested in conventional goals[...] It's a term of derision and also the ultimate compliment."[9]

Fred Shapiro thinks that "the common theory that 'hacker' originally was a benign term and the malicious connotations of the word were a later perversion is untrue." He found out that the malicious connotations were present at MIT in 1963 already (quoting The Tech, a MIT Student Magazine) and then referred to unauthorized users of the telephone network,[10][11] that is, the phreaker movement that developed into the computer security hacker subculture of today.

In computer security, a hacker is someone who focuses on security

mechanisms of computer and network systems. While including those who

endeavor to strengthen such mechanisms, it is more often used by the mass media

and popular culture to refer to those who seek access despite these

security measures. That is, the media portrays the 'hacker' as a

villain. Nevertheless, parts of the subculture see their aim in

correcting security problems and use the word in a positive sense. They

operate under a code,

which acknowledges that breaking into other people's computers is bad,

but that discovering and exploiting security mechanisms and breaking

into computers is still an interesting activity that can be done

ethically and legally. Accordingly, the term bears strong connotations

that are favorable or pejorative, depending on the context.

The subculture around such hackers is termed network hacker subculture, hacker scene or computer underground. It initially developed in the context of phreaking during the 1960s and the microcomputer BBS scene of the 1980s. It is implicated with 2600: The Hacker Quarterly and the alt.2600 newsgroup.

In 1980, an article in the August issue of Psychology Today (with commentary by Philip Zimbardo) used the term "hacker" in its title: "The Hacker Papers". It was an excerpt from a Stanford Bulletin Board discussion on the addictive nature of computer use. In the 1982 film Tron, Kevin Flynn (Jeff Bridges) describes his intentions to break into ENCOM's computer system, saying "I've been doing a little hacking here". CLU is the software he uses for this. By 1983, hacking in the sense of breaking computer security had already been in use as computer jargon,[12] but there was no public awareness about such activities.[13] However, the release of the film WarGames that year, featuring a computer intrusion into NORAD, raised the public belief that computer security hackers (especially teenagers) could be a threat to national security. This concern became real when, in the same year, a gang of teenage hackers in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, known as The 414s, broke into computer systems throughout the United States and Canada, including those of Los Alamos National Laboratory, Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and Security Pacific Bank.[14] The case quickly grew media attention,[14][15] and 17-year-old Neal Patrick emerged as the spokesman for the gang, including a cover story in Newsweek entitled "Beware: Hackers at play", with Patrick's photograph on the cover.[16] The Newsweek article appears to be the first use of the word hacker by the mainstream media in the pejorative sense.

Pressured by media coverage, congressman Dan Glickman called for an investigation and began work on new laws against computer hacking.[17][18] Neal Patrick testified before the U.S. House of Representatives on September 26, 1983, about the dangers of computer hacking, and six bills concerning computer crime were introduced in the House that year.[19] As a result of these laws against computer criminality, white hat, grey hat and black hat hackers try to distinguish themselves from each other, depending on the legality of their activities. These moral conflicts are expressed in The Mentor's "The Hacker Manifesto", published 1986 in Phrack.

Use of the term hacker meaning computer criminal was also advanced by the title "Stalking the Wily Hacker", an article by Clifford Stoll in the May 1988 issue of the Communications of the ACM. Later that year, the release by Robert Tappan Morris, Jr. of the so-called Morris worm provoked the popular media to spread this usage. The popularity of Stoll's book The Cuckoo's Egg, published one year later, further entrenched the term in the public's consciousness.

The programmer subculture of hackers disassociates from the mass media's pejorative use of the word 'hacker' referring to computer security, and usually prefer the term 'cracker' for that meaning. Complaints about supposed mainstream misuse started as early as 1983, when media used "hacker" to refer to the computer criminals involved in the 414s case.[20]

In the programmer subculture of hackers, a computer hacker is a person who enjoys designing software and building programs with a sense for aesthetics and playful cleverness. The term hack in this sense can be traced back to "describe the elaborate college pranks that...students would regularly devise" (Levy, 1984 p. 10). To be considered a 'hack' was an honour among like-minded peers as "to qualify as a hack, the feat must be imbued with innovation, style and technical virtuosity" (Levy, 1984 p. 10) The MIT's Tech Model Railroad Club Dictionary defined hack in 1959 (not yet in a computer context) as "1) an article or project without constructive end; 2) a project undertaken on bad self-advice; 3) an entropy booster; 4) to produce, or attempt to produce, a hack(3)." "hacker" was defined as "one who hacks, or makes them." Much of the TMRC's jargon was later imported into early computing culture, because the club started using a DEC PDP-1 and applied its local model railroad slang in this computing context. Despite being incomprehensible to outsiders, the slang became popular in MIT's computing environments outside the club. Other examples of jargon imported from the club are 'losing' "when a piece of equipment is not working"[21] and 'munged' "when a piece of equipment is ruined".[21]

According to Eric S. Raymond,[22] the Open source and Free Software hacker subculture developed in the 1960s among 'academic hackers'[23] working on early minicomputers in computer science environments in the United States.

Hackers were influenced by and absorbed many ideas of key technological developments and the people associated with them. Most notable is the technical culture of the pioneers of the Arpanet, starting in 1969. The PDP-10 machine AI at MIT, which was running the ITS operating system and which was connected to the Arpanet, provided an early hacker meeting point. After 1980 the subculture coalesced with the culture of Unix. Since the mid-1990s, it has been largely coincident with what is now called the free software and open source movement.

Many programmers have been labeled "great hackers",[24] but the specifics of who that label applies to is a matter of opinion. Certainly major contributors to computer science such as Edsger Dijkstra and Donald Knuth, as well as the inventors of popular software such as Linus Torvalds (Linux), and Dennis Ritchie and Ken Thompson (the C programming language) are likely to be included in any such list; see also List of programmers. People primarily known for their contributions to the consciousness of the programmer subculture of hackers include Richard Stallman, the founder of the free software movement and the GNU project, president of the Free Software Foundation and author of the famous Emacs text editor as well as the GNU Compiler Collection (GCC), and Eric S. Raymond, one of the founders of the Open Source Initiative and writer of the famous text The Cathedral and the Bazaar and many other essays, maintainer of the Jargon File (which was previously maintained by Guy L. Steele, Jr.).

Within the computer programmer subculture of hackers, the term hacker is also used for a programmer who reaches a goal by employing a series of modifications to extend existing code or resources. In this sense, it can have a negative connotation of using inelegant kludges to accomplish programming tasks that are quick, but ugly, inelegant, difficult to extend, hard to maintain and inefficient. This derogatory form of the noun "hack" derives from the everyday English sense "to cut or shape by or as if by crude or ruthless strokes" [Merriam-Webster] and is even used among users of the positive sense of "hacker" who produces "cool" or "neat" hacks. In other words to "hack" at an original creation, as if with an axe, is to force-fit it into being usable for a task not intended by the original creator, and a "hacker" would be someone who does this habitually. (The original creator and the hacker may be the same person.) This usage is common in both programming, engineering and building. In programming, hacking in this sense appears to be tolerated and seen as a necessary compromise in many situations. Some argue that it should not be, due to this negative meaning; others argue that some kludges can, for all their ugliness and imperfection, still have "hack value". In non-software engineering, the culture is less tolerant of unmaintainable solutions, even when intended to be temporary, and describing someone as a "hacker" might imply that they lack professionalism. In this sense, the term has no real positive connotations, except for the idea that the hacker is capable of doing modifications that allow a system to work in the short term, and so has some sort of marketable skills. There is always, however, the understanding that a more skillful, or technical, logician could have produced successful modifications that would not be considered a "hack-job". The definition is similar to other, non-computer based, uses of the term "hack-job". For instance, a professional modification of a production sports car into a racing machine would not be considered a hack-job, but a cobbled together backyard mechanic's result could be. Even though the outcome of a race of the two machines could not be assumed, a quick inspection would instantly reveal the difference in the level of professionalism of the designers. The adjective associated with hacker is "hackish" (see the Jargon file).

In a very universal sense, hacker also means someone who makes things work beyond perceived limits in a clever way in general, without necessarily referring to computers, especially at the MIT.[3] That is, people who apply the creative attitude of software hackers in fields other than computing. This includes even activities that predate computer hacking, for example reality hackers or urban spelunkers (exploring undocumented or unauthorized areas in buildings). One specific example are clever pranks[25] traditionally perpetrated by MIT students, with the perpetrator being called hacker. For example, when MIT students surreptitiously put a fake police car atop the dome on MIT's Building 10,[26] that was a hack in this sense, and the students involved were therefore hackers. Another type of hacker is now called a reality hacker. More recent examples of usage for almost any type of playful cleverness are wetware hackers ("hack your brain"), media hackers and "hack your reputation". In a similar vein, a "hack" may refer to a math hack, that is, a clever solution to a mathematical problem. The GNU General Public License has been described as[who?] a copyright hack because it cleverly uses the copyright laws for a purpose the lawmakers did not foresee. All of these uses now also seem to be spreading beyond MIT as well.

A large overlaps between hobbyist hackers and the programmer subculture hackers existed during the Homebrew Club's days, but the interests and values of both communities somewhat diverged. Today, the hobbyists focus on commercial computer and video games, software cracking and exceptional computer programming (demo scene). Also of interest to some members of this group is the modification of computer hardware and other electronic devices, see modding.

Electronics hobbyists working on machines other than computers also

fall into this category. This includes people who do simple

modifications to graphing calculators, video game consoles, electronic musical keyboards or other device (see CueCat

for a notorious example) to expose or add functionality to a device

that was unintended for use by end users by the company who created it. A

number of techno musicians have modified 1980s-era Casio SK-1 sampling keyboards to create unusual sounds by doing circuit bending:

connecting wires to different leads of the integrated circuit chips.

The results of these DIY experiments range from opening up previously

inaccessible features that were part of the chip design to producing the

strange, dis-harmonic digital tones that became part of the techno

music style. Companies take different attitudes towards such practices,

ranging from open acceptance (such as Texas Instruments for its graphing calculators and Lego for its Lego Mindstorms robotics gear) to outright hostility (such as Microsoft's attempts to lock out Xbox hackers or the DRM routines on Blu-ray Disc players designed to sabotage compromised players.[citation needed])

In this context, a "hack" refers to a program that (sometimes illegally) modifies another program, often a video game, giving the user access to features otherwise inaccessible to them. As an example of this use, for Palm OS users (until the 4th iteration of this operating system), a "hack" refers to an extension of the operating system which provides additional functionality. Term also refers to those people who cheat on video games using special software. This can also refer to the jailbreaking of iPods.

According to Raymond, hackers from the programmer subculture usually work openly and use their real name, while computer security hackers prefer secretive groups and identity-concealing aliases.[29] Also, their activities in practice are largely distinct. The former focus on creating new and improving existing infrastructure (especially the software environment they work with), while the latter primarily and strongly emphasize the general act of circumvention of security measures, with the effective use of the knowledge (which can be to report and help fixing the security bugs, or exploitation for criminal purpose) being only rather secondary. The most visible difference in these views was in the design of the MIT hackers' Incompatible Timesharing System, which deliberately did not have any security measures.

There are some subtle overlaps, however, since basic knowledge about computer security is also common within the programmer subculture of hackers. For example, Ken Thompson noted during his 1983 Turing Award lecture that it is possible to add code to the UNIX "login" command that would accept either the intended encrypted password or a particular known password, allowing a back door into the system with the latter password. He named his invention the "Trojan horse". Furthermore, Thompson argued, the C compiler itself could be modified to automatically generate the rogue code, to make detecting the modification even harder. Because the compiler is itself a program generated from a compiler, the Trojan horse could also be automatically installed in a new compiler program, without any detectable modification to the source of the new compiler. However, Thompson disassociated himself strictly from the computer security hackers: "I would like to criticize the press in its handling of the 'hackers,' the 414 gang, the Dalton gang, etc. The acts performed by these kids are vandalism at best and probably trespass and theft at worst. ... I have watched kids testifying before Congress. It is clear that they are completely unaware of the seriousness of their acts."[30]

The programmer subculture of hackers sees secondary circumvention of security mechanisms as legitimate if it is done to get practical barriers out of the way for doing actual work. In special forms, that can even be an expression of playful cleverness.[31] However, the systematic and primary engagement in such activities is not one of the actual interests of the programmer subculture of hackers and it does not have significance in its actual activities, either.[29] A further difference is that, historically, members of the programmer subculture of hackers were working at academic institutions and used the computing environment there. In contrast, the prototypical computer security hacker had access exclusively to a home computer and a modem. However since the mid-1990s, with home computers that could run Unix-like operating systems and with inexpensive internet home access being available for the first time, many people from outside of the academic world started to take part in the programmer subculture of hacking.

Since the mid-1980s, there are some overlaps in ideas and members with the computer security hacking community. The most prominent case is Robert T. Morris, who was a user of MIT-AI, yet wrote the Morris worm. The Jargon File hence calls him "a true hacker who blundered".[32] Nevertheless, members of the programmer subculture have a tendency to look down on and disassociate from these overlaps. They commonly refer disparagingly to people in the computer security subculture as crackers, and refuse to accept any definition of hacker that encompasses such activities. The computer security hacking subculture on the other hand tends not to distinguish between the two subcultures as harshly, instead acknowledging that they have much in common including many members, political and social goals, and a love of learning about technology. They restrict the use of the term cracker to their categories of script kiddies and black hat hackers instead.

All three subcultures have relations to hardware modifications. In the early days of network hacking, phreaks were building blue boxes and various variants. The programmer subculture of hackers has stories about several hardware hacks in its folklore, such as a mysterious 'magic' switch attached to a PDP-10 computer in MIT's AI lab, that, when turned off, crashed the computer.[33] The early hobbyist hackers built their home computers themselves, from construction kits. However, all these activities have died out during the 1980s, when the phone network switched to digitally controlled switchboards, causing network hacking to shift to dialing remote computers with modems, when pre-assembled inexpensive home computers were available, and when academic institutions started to give individual mass-produced workstation computers to scientists instead of using a central timesharing system. The only kind of widespread hardware modification nowadays is case modding.

An encounter of the programmer and the computer security hacker subculture occurred at the end of the 1980s, when a group of computer security hackers, sympathizing with the Chaos Computer Club (who disclaimed any knowledge in these activities), broke into computers of American military organizations and academic institutions. They sold data from these machines to the Soviet secret service, one of them in order to fund his drug addiction. The case could be solved when Clifford Stoll, a scientist working as a system administrator, found ways to log the attacks and to trace them back (with the help of many others). 23, a German film adaption with fictional elements, shows the events from the attackers' perspective. Stoll described the case in his book The Cuckoo's Egg and in the TV documentary The KGB, the Computer, and Me from the other perspective. According to Eric S. Raymond, it "nicely illustrates the difference between 'hacker' and 'cracker'. Stoll's portrait of himself, his lady Martha, and his friends at Berkeley and on the Internet paints a marvelously vivid picture of how hackers and the people around them like to live and how they think."[34]

- (în vernacular) cel care sparge/se infiltrează în calculatoarele altora[1][2] (cuvântul corect pentru asta este de fapt cracker,[2][3][4][5] sau sinonimul său „pălărie neagră”).[6] Acest cuvânt provine de la ocupația favorită a crackerilor și anume de a sparge parole. Se poate vorbi atât de crackeri care sparg programe shareware sau altfel de software sau media protejate, cât și de crackeri care sparg calculatoare și obțin accesul la informații confidențiale (de exemplu numere de cărți de credit), sau virusează calculatorul altora (de exemplu, pentru a-l folosi drept fabrică de spam sau a găzdui pornografie, de obicei ilegală, în scop de câștig comercial); sinonime: spărgător de programe și/sau spărgător de calculatoare;

- există o variantă de crackeri-hackeri care sparg sisteme informatice doar pentru a demonstra existența unor vulnerabiltăți în sistem, pe urmă comunicând proprietarilor/producătorilor sistemelor existența acestor exploituri și modul în care se pot proteja de astfel de atacuri (ei sunt numiți crackeri etici sau hackeri etici). Ei pot fi numiți și pălării albe (în limba engleză, „white hats”). Prin urmare, hacker etic este cineva care poate intra într-un sistem informatic pe alte căi decât cele oficiale, pentru a demonstra existența unor probleme de securitate și eventual a le remedia/elimina. Câteva exemple, chiar din România sunt (în ordine alfabetică): Alien Hackers, DefCamp , HackersBlog și Sysboard.

- (super)experți în tehnologii software și/sau hardware;[3]

- hobbyiști care trec peste granițele aparente existente în diverse dispozitive hardware și/sau în diverse programe de calculator.[2][3][7]

Ziarele americane au publicat numeroase articole care spuneau Un anumit hacker a spart un anumit sistem informatic, însemnând de fapt Un anumit expert în calculatoare a spart un anumit sistem informatic.[8][9] Folosirea termenului este corectă, căci dacă oamenii respectivi n-ar fi fost experți în calculatoare, nu ar fi putut sparge astfel de sisteme (pe atunci nu apăruseră haxorii, adică crackeri care nu se pricep la programare și utilizează pentru spart programele făcute de alții). Dar asocierea cuvântului hacker (expert în calculatoare) cu operațiuni imorale și/sau ilegale este doar „între urechile” publicului larg, care a citit astfel de articole, și a ramas cu impresia greșită (prejudecata, stereotipul) că hackerii (în general) ar fi niște infractori.

Se mai pot deosebi următoarele sensuri specializate (din subcultura informaticienilor) ale cuvântului hacker:

- cineva care cunoaște foarte bine un limbaj de programare sau mediu de programare, astfel încât poate scrie un program fără niciun efort aparent;

- cineva care inventează, proiectează, dezvoltă, implementează, testează sau îmbunătățește o tehnologie;

- cineva care oferă soluții neconvenționale dar adecvate împotriva exploiturilor, erorilor și ale unor alt fel de probleme, cu ajutorul mijloacelor disponibile.

Că a fi hacker sau cracker sunt două lucruri diferite, o arată hackerii Steve Gibson și Eric Steven Raymond. Gibson precizează:

Dacă mulți infractori informatici nu sunt prinși este din cauză că Poliția nu apreciază gravitatea unor astfel de fapte. Conform lui Steve Gibson, costul unei investigații FBI asupra unei infracțiuni informatice se ridică la USD 200 000,[12] ceea ce face FBI-ul să urmărească doar infracțiunile informatice foarte grave; dacă dauna este sub USD 5000 se consideră că nu s-a comis nicio infracțiune.[12] În schimb, costurile procesului Ministerului Public olandez contra lui Holleeder (un infractor clasic) au fost estimate la cel puțin 70 de milioane de Euro.[necesită citare]

Motivațiile tipice pentru spărgătorii de calculatoare sunt: bani, distracție, ego, cauză social-politică (activism), admitere într-un anume grup social și obținerea unui statut social.[13] Banii pot fi obținuți de exemplu prin a afla numere de cărți de credit sau prin șantajarea unor firme, amenințate cu blocarea sitului lor de internet.[13] Distracție înseamnă că motivația de a sparge sisteme informatice nu este cea de a produce daune, ci instinctul de joc al lui Homo ludens, adică comportamentul jucăuș și de a face glume.[13] Ego: motivația constă în satisfacția datorată învingerii unor bariere hard/soft prin creativitate informatică.[13] Căuzașii (hacktiviștii) se folosesc de puterea pe care spargerea de calculatoare le-o conferă pentru a promova cauza în care cred cu tărie (drepturile omului, drepturile animalelor, adoptarea Sharia, etc.).[13] Intrarea în grupul social al hackerilor este determinată de merite dovedite în activitatea proprie ca hacker, ageamii nefiind admiși în astfel de cercuri.[13] Statutul social în ciberspațiu poate fi obținut prin a comunica altora experiența obținută de hacker, făcând astfel dovada priceperii proprii, și a înainta prin astfel astfel de conversații și contribuții în ierarhia socială a diverselor canale IRC pe care discută hackerii.[13]

Referindu-ne la hackerii care comit infracțiuni, numiți mai corect crackeri sau spărgători de calculatoare, din informațiile publicate de FBI nu ar rezulta că cei care comit infracțiuni informatice ar avea vreo etică respectabilă, ei comițând tot felul de fapte care pe lângă a fi infracțiuni sunt fapte profund antisociale (furt, fraudă, escrocherie, violarea dreptului la privacy, furt de identitate, șantaj, hărțuire, etc.) iar păgubiții sunt adesea oameni de rând, nu mari companii cărora li s-ar putea reproșa ceva.[14][15]

După Sam Williams, a existat într-adevăr o etică a hackerilor,[8] dar pe vremea respectivă hackerii nu erau infractori, ci doar informaticieni motivați de curiozitate și spirit de joacă. Epitetul de hacker aplicat infractorilor ar proveni după el din faptul că ziarele au luat notă că primii infractori informatici care au fost judecați făceau referire la etica hackerilor (ne-infractori) în apărarea proprie.[8]

Автор:

Славик Богачёв

Хакерами называют, например, Линуса Торвальдса, Ричарда Столлмана, Ларри Уолла, Дональда Кнута, Бьёрна Страуструпа, Эрика Рэймонда[источник не указан 571 день], Эндрю Таненбаума и других создателей открытых систем мирового уровня. В России ярким примером хакера является Крис Касперски.

Иногда этот термин применяют для обозначения специалистов вообще — в том контексте, что они обладают очень детальными знаниями в каких-либо вопросах или имеют достаточно нестандартное и конструктивное мышление. С момента появления этого слова в форме компьютерного термина (1960-е годы), у него появлялись новые, часто различные значения.

Содержание[убрать] |

[править] Различные значения слова

Jargon File даёт следующее определение[1]:Хакер (изначально — кто-либо, делающий мебель при помощи топора):

- Человек, увлекающийся исследованием подробностей (деталей) программируемых систем, изучением вопроса повышения их возможностей, в противоположность большинству пользователей, которые предпочитают ограничиваться изучением необходимого минимума. RFC 1983 усиливает это определение следующим образом: «Человек, наслаждающийся доскональным пониманием внутренних действий систем, компьютеров и компьютерных сетей в частности».

- Кто-либо программирующий с энтузиазмом (даже одержимо) или любящий программировать, а не просто теоретизировать о программировании.

- Человек, способный ценить и понимать хакерские ценности.

- Человек, который силён в быстром программировании.

- Эксперт по отношению к определённой компьютерной программе или кто-либо часто работающий с ней; пример: «хакер Unix». (Определения 1—5 взаимосвязаны, так что один человек может попадать под несколько из них.)

- Эксперт или энтузиаст любого рода. Кто-либо может считаться «хакером астрономии», например.

- Кто-либо любящий интеллектуальные испытания, заключающиеся в творческом преодолении или обходе ограничений.

- (неодобрительно) Злоумышленник, добывающий конфиденциальную информацию в обход систем защиты (например, «хакер паролей», «сетевой хакер»). Правильный термин — взломщик, крэкер (англ. cracker).

В последнее время слово «хакер» имеет менее общее определение — этим термином называют всех сетевых взломщиков, создателей компьютерных вирусов и других компьютерных преступников, таких как кардеры, крэкеры, скрипт-кидди. Многие компьютерные взломщики по праву могут называться хакерами, потому как действительно соответствуют всем (или почти всем) вышеперечисленным определениям слова «хакер». Хотя в каждом отдельном случае следует понимать, в каком смысле используется слово «хакер» — в смысле «знаток» или в смысле «взломщик».

В ранних значениях, в компьютерной сфере, «хакерами» называли программистов с более низкой квалификацией, которые писали программы соединяя вместе готовые «куски» программ других программистов, что приводило к увеличению объёмов и снижению быстродействия программ. Процессоры в то время были «тихоходами» по сравнению с современными, а HDD объёмом 4,7 Гб был «крутым» для ПК. И было бы некорректно говорить о том, что «хакеры» исправляли ошибки в чужих программах.

[править] Ценности хакеров

Основная статья: Хакерская ценность

В среде хакеров принято ценить время своё и других хакеров («не

изобретать велосипед»), что, в частности, подразумевает необходимость

делиться своими достижениями, создавая свободные и/или открытые программы.[править] Социокультурные аспекты

Возникновение хакерской культуры тесно связано с пользовательскими группами мини-компьютеров PDP и ранних микрокомпьютеров.Брюс Стерлинг в своей работе «Охота на хакеров»[2] возводит хакерское движение к движению телефонных фрикеров, которое сформировалось вокруг американского журнала TAP, изначально принадлежавшего молодёжной партии йиппи (Youth International Party), которая явно сочувствовала коммунистам. Журнал TAP представлял собою техническую программу поддержки (Technical Assistance Program) партии Эбби Хоффмана (Abbie Hoffman), помогающую неформалам бесплатно общаться по межгороду и производить политические изменения в своей стране, порой несанкционированные властями.

Персонажи-хакеры достаточно распространены в научной фантастике, особенно в жанре киберпанк. В этом контексте хакеры обычно являются протагонистами, которые борются с угнетающими структурами, которыми преимущественно являются транснациональные корпорации. Борьба обычно идёт за свободу и доступ к информации. Часто в подобной борьбе звучат коммунистические или анархические лозунги.

В России, Европе и Америке взлом компьютеров, уничтожение информации, создание и распространение компьютерных вирусов и вредоносных программ преследуется законом. Злостные взломщики согласно международным законам по борьбе с киберпреступностью подлежат экстрадиции подобно военным преступникам.

[править] Исторические причины существования различий в значениях слова «хакер»

Значение слова «хакер» в первоначальном его понимании, вероятно, возникло в стенах MIT в 1960-х задолго до широкого распространения компьютеров. Тогда оно являлось частью местного сленга и могло обозначать простое, но грубое решение какой-либо проблемы; чертовски хитрую проделку студентов (обычно автора и называли хакером). До того времени слова «hack» и «hacker» использовались по разным поводам безотносительно к компьютерной технике вообще.Первоначально появилось жаргонное слово «to hack» (рубить, кромсать). Оно означало процесс внесения изменений «на лету» в свою или чужую программу (предполагалось, что имеются исходные тексты программы). Отглагольное существительное «hack» означало результаты такого изменения. Весьма полезным и достойным делом считалось не просто сообщить автору программы об ошибке, а сразу предложить ему такой хак, который её исправляет. Слово «хакер» изначально произошло именно отсюда.

Хак, однако, не всегда имел целью исправление ошибок — он мог менять поведение программы вопреки воле её автора. Именно подобные скандальные инциденты, в основном, и становились достоянием гласности, а понимание хакерства как активной обратной связи между авторами и пользователями программ никогда журналистов не интересовало. Затем настала эпоха закрытого программного кода, исходные тексты многих программ стали недоступными, и положительная роль хакерства начала сходить на нет — огромные затраты времени на хак закрытого исходного кода могли быть оправданы только очень сильной мотивацией — такой, как желание заработать деньги или скандальную популярность.

В результате появилось новое, искажённое понимание слова «хакер»: оно означает злоумышленника, использующего обширные компьютерные знания для осуществления несанкционированных, иногда вредоносных действий в компьютере — взлом компьютеров, написание и распространение компьютерных вирусов. Впервые в этом значении слово «хакер» было употреблено Клиффордом Столлом в его книге «Яйцо кукушки», а его популяризации немало способствовал голливудский кинофильм «Хакеры». В подобном компьютерном сленге слова «хак», «хакать» обычно относятся ко взлому защиты компьютерных сетей, веб-серверов и тому подобному.

Отголоском негативного восприятия понятия «хакер» является слово «кулхацкер» (от англ. cool hacker), получившее распространение в отечественной околокомпьютерной среде практически с ростом популярности исходного слова. Этим термином обычно называют дилетанта, старающегося походить на профессионала хотя бы внешне — при помощи употребления якобы «профессиональных» хакерских терминов и жаргона, использования «типа хакерских» программ без попыток разобраться в их работе и т. п. Название «кулхацкер» иронизирует над тем, что такой человек, считая себя крутым хакером (англ. cool hacker), настолько безграмотен, что даже не может правильно прочитать по-английски то, как он себя называет. В англоязычной среде такие люди получили наименование «скрипт-кидди».

Некоторые из личностей, известных как поборники свободного и открытого программного обеспечения — например, Ричард Столлман — призывают к использованию слова «хакер» только в первоначальном смысле.

Весьма подробные объяснения термина в его первоначальном смысле приведены в статье Эрика Рэймонда «Как стать хакером»[3]. Также Эрик Рэймонд предложил в октябре 2003 года эмблему для хакерского сообщества — символ «глайдера» (glider) из игры «Жизнь». Поскольку сообщество хакеров не имеет единого центра или официальной структуры, предложенный символ нельзя считать официальным символом хакерского движения. По этим же причинам невозможно судить о распространённости этой символики среди хакеров — хотя вполне вероятно, что какая-то часть хакерского сообщества приняла её.

[править] Хакеры в литературе

- Сергей Лукьяненко в романе «Лабиринт отражений» в качестве эпиграфа привёл отрывок из вымышленного им «Гимна хакеров»[4].

- Крис Касперски. Введение. Об авторе // Компьютерные вирусы изнутри и снаружи. — СПб.: Питер, 2006. — С. 527. — ISBN 5-469-00982-3

- Джеффри Дивер. Синее нигде = The Blue Nowhere. — 2001.

[править] Хакеры в кино

- Виртуальная реальность / VR.5 (1995)

- Сеть (1995)

- Хакеры (1995)

- Нирвана (1997)

- Повелитель сети / Skyggen (1998)

- Матрица (1999)

- Пираты Силиконовой долины (1999)

- Взлом (2000)

- Антитраст / Antitrust (2001)

- Медвежатник (2001)

- Охотник за кодом / Storm Watch (Code Hunter) (2001)

- Пароль «Рыба-меч» (2001)

- Энигма (2001)

- Версия 1.0 (2004)

- Огненная стена (2006)

- Сеть 2.0 / The Net 2.0 (2006)

- Хоттабыч (2006)

- Крепкий орешек 4.0 (2007)

- Сеть (многосерийный фильм, Россия) (2007)

- Bloody Monday (2008) — дорама по сюжету одноимённой манги

- Девушка с татуировкой дракона (2009)

- Социальная сеть (2010)

[править] Известные люди

[править] Известные хакеры (в первоначальном смысле слова)

- Линус Торвальдс — создатель открытого ядра Linux[5]

- Ларри Уолл — создатель языка и системы программирования Perl

- Ричард Столлман — основатель концепции свободного программного обеспечения

- Джеф Раскин — специалист по компьютерным интерфейсам, наиболее известен как инициатор проекта Macintosh в конце 1970-x.

- Эрик Рэймонд основатель Open Source Initiative

- Тим Бернерс-Ли — изобретатель Всемирной паутины (WWW), получивший немало наград, включая Премию тысячелетия в области технологий.

[править] Известные взломщики

- Роберт Моррис — автор Червя Морриса 1988 года. (На самом деле червь Морриса был лабораторным опытом, поэтому взломщиком его можно считать условно.)[6]

- Адриан Ламо — известен взломом Yahoo, Citigroup, Bank of America и Cingular.

- Джонатан Джеймс — американский хакер, стал первым несовершеннолетним, осужденным за хакерство.

- Джон Дрейпер — один из первых хакеров в истории компьютерного мира.

- Кевин Поулсен — взломал базу данных ФБР и получил доступ к засекреченной информации, касающейся прослушивания телефонных разговоров. Поулсен долго скрывался, изменяя адреса и даже внешность, но в конце концов он был пойман и осужден на 5 лет. После выхода из тюрьмы работал журналистом, затем стал главным редактором Wired News. Его самая популярная статья описывает процесс идентификации 744 сексуальных маньяков по их профилям в MySpace.

- Гэри Маккиннон — обвиняется во взломе 53-х компьютеров Пентагона и НАСА в 2001—2002 годах в поисках информации об НЛО.

[править] Известные хакеры-писатели

- Крис Касперски — автор популярных книг и статей на компьютерную тематику.

- Кевин Митник — самый известный компьютерный взломщик, ныне писатель и специалист в области информационной безопасности.

[править] См. также

- Манифест хакера

- Фрикер

- Крэкер

- Хакерская атака

- Компьютерный терроризм

- Самоуправляемый общественный центр

- The Hacker's Handbook

- Журнал «Хакер»

- Лайфхакер

- Информационная безопасность

- Защита информации

- Информатика

- Antifa Hack Team

- Преступления в сфере информационных технологий

- Скрипт-кидди

- Гик

[править] Примечания

- ↑ Hacker в «Энциклопедическом словаре хакера» (Jargon File) (англ.)

- ↑ Bruce Sterling. The Hacker Crackdown: Law and Disorder on the Electronic Frontier. — Spectra Books, 1992. — ISBN 0-553-56370-X См. русский перевод на BugTraq

- ↑ Эрик Рэймонд. Как стать хакером (англ.) = How To Become A Hacker.

- ↑ Сергей Лукьяненко. Лабиринт отражений.

- ↑

«Вообще-то, обычно я избегаю слова „хакер“. В личном разговоре с технарями я еще могу назвать себя хакером. Но в последнее время смысл этого слова изменился: так стали называть мальчишек, которые от нечего делать заняты электронным взломом корпоративных ВЦ вместо того, чтобы помогать работе местных библиотек или уж, на худой конец, бегать за девочками.»— Linus Torvalds. Just for fun

- ↑ Пол Грэм в своей статье (Грэм П. Великие хакеры // Спольски Дж. Х. Лучшие примеры разработки ПО : книга. — СПб.: Питер, 2007. — С. 77—87. — ISBN 5-469-01291-3.) приводит Морриса в качестве примера хакера в первоначальном смысле слова.

[править] Литература

- Иван Скляров. Головоломки для хакера. — СПб.: БХВ-Петербург, 2005. — С. 320. — ISBN 5-94175-562-9

- Максим Кузнецов, Игорь Симдянов. Головоломки на PHP для хакера. — 2 изд. — СПб.: БХВ-Петербург, 2008. — С. 554. — ISBN 978-5-9775-0204-7

- Джоел Скембрей, Стюарт Мак-Клар. Секреты хакеров. Безопасность Microsoft Windows Server 2003 — готовые решения = Hacking Exposed Windows® Server 2003. — М.: Вильямс, 2004. — С. 512. — ISBN 0-07-223061-4

- Стюарт Мак-Клар, Джоэл Скембрей, Джордж Курц. Секреты хакеров. Безопасность сетей — готовые решения = Hacking Exposed: Network Security Secrets & Solutions. — М.: Вильямс, 2004. — С. 656. — ISBN 0-07-222742-7

- Майк Шиффман. Защита от хакеров. Анализ 20 сценариев взлома = Hacker's Challenge: Test Your Incident Response Skills Using 20 Scenarios. — М.: Вильямс, 2002. — С. 304. — ISBN 0-07-219384-0

- Стивен Леви. Хакеры, герои компьютерной революции = Hackers, Heroes of the computer revolution. — A Penguin Book Technology, 2002. — С. 337. — ISBN 0-14-100051-1

- Скородумова О. Б. Хакеры // Знание. Понимание. Умение : журнал. — М., 2005. — № 4. — С. 159—161.

- Савчук И. С. Сети, браузер, два ствола… // Компьютерные вести : газета. — 2010.

[править] Ссылки

- «Хаки» MIT (англ.)

- Российский журнал «Хакер»

- People committed to circumvention of computer security. This primarily concerns unauthorized remote computer break-ins via a communication networks such as the Internet (Black hats), but also includes those who debug or fix security problems (White hats), and the morally ambiguous Grey hats. See Hacker (computer security).

- A community of enthusiast computer programmers and systems designers, originated in the 1960s around the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's (MIT's) Tech Model Railroad Club (TMRC) and MIT Artificial Intelligence Laboratory.[2] This community is notable for launching the free software movement. The World Wide Web and the Internet itself are also hacker artifacts.[3] The Request for Comments RFC 1392 amplifies this meaning as "[a] person who delights in having an intimate understanding of the internal workings of a system, computers and computer networks in particular." See Hacker (programmer subculture).

- The hobbyist home computing community, focusing on hardware in the late 1970s (e.g. the Homebrew Computer Club[4]) and on software (video games,[5] software cracking, the demoscene) in the 1980s/1990s. The community included Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, Bill Gates and Paul Allen and created the personal computing industry.[6] See Hacker (hobbyist).

Today, mainstream usage of "hacker" mostly refers to computer criminals, due to the mass media usage of the word since the 1980s. This includes what hacker slang calls "script kiddies," people breaking into computers using programs written by others, with very little knowledge about the way they work. This usage has become so predominant that the general public is unaware that different meanings exist. While the self-designation of hobbyists as hackers is acknowledged by all three kinds of hackers, and the computer security hackers accept all uses of the word, people from the programmer subculture consider the computer intrusion related usage incorrect, and emphasize the difference between the two by calling security breakers "crackers" (analogous to a safecracker).

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Hacker definition controversy

|

|

This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2011) |

- as someone who is able to subvert computer security, if doing so for malicious purposes it can also be called a cracker.

- a member of the Unix or the free and open source software programming subcultures or one who uses such a style of software or hardware development.

As a result of this difference, the definition is the subject of heated controversy. The wider dominance of the pejorative connotation is resented by many who object to the term being taken from their cultural jargon and used negatively,[8] including those who have historically preferred to self-identify as hackers. Many advocate using the more recent and nuanced alternate terms when describing criminals and others who negatively take advantage of security flaws in software and hardware. Others prefer to follow common popular usage, arguing that the positive form is confusing and unlikely to become widespread in the general public. A minority still stubbornly use the term in both original senses despite the controversy, leaving context to clarify (or leave ambiguous) which meaning is intended. It is noteworthy, however, that the positive definition of hacker was widely used as the predominant form for many years before the negative definition was popularized. "Hacker" can therefore be seen as a shibboleth, identifying those who use the technically oriented sense (as opposed to the exclusively intrusion-oriented sense) as members of the computing community.

A possible middle ground position has been suggested, based on the observation that "hacking" describes a collection of skills which are used by hackers of both descriptions for differing reasons. The analogy is made to locksmithing, specifically picking locks, which — aside from its being a skill with a fairly high tropism to 'classic' hacking — is a skill which can be used for good or evil. The primary weakness of this analogy is the inclusion of script kiddies in the popular usage of "hacker", despite the lack of an underlying skill and knowledge base. Sometimes, hacker also is simply used synonymous to geek: "A true hacker is not a group person. He's a person who loves to stay up all night, he and the machine in a love-hate relationship... They're kids who tended to be brilliant but not very interested in conventional goals[...] It's a term of derision and also the ultimate compliment."[9]

Fred Shapiro thinks that "the common theory that 'hacker' originally was a benign term and the malicious connotations of the word were a later perversion is untrue." He found out that the malicious connotations were present at MIT in 1963 already (quoting The Tech, a MIT Student Magazine) and then referred to unauthorized users of the telephone network,[10][11] that is, the phreaker movement that developed into the computer security hacker subculture of today.

[edit] Computer security hackers

Main article: Hacker (computer security)

| This article is part of a series on |

| Computer hacking |

|---|

| History |

| Hacker ethic |

| Computer crime |

| Hacking tools |

| Malware |

| Computer security |

| Groups |

The subculture around such hackers is termed network hacker subculture, hacker scene or computer underground. It initially developed in the context of phreaking during the 1960s and the microcomputer BBS scene of the 1980s. It is implicated with 2600: The Hacker Quarterly and the alt.2600 newsgroup.

In 1980, an article in the August issue of Psychology Today (with commentary by Philip Zimbardo) used the term "hacker" in its title: "The Hacker Papers". It was an excerpt from a Stanford Bulletin Board discussion on the addictive nature of computer use. In the 1982 film Tron, Kevin Flynn (Jeff Bridges) describes his intentions to break into ENCOM's computer system, saying "I've been doing a little hacking here". CLU is the software he uses for this. By 1983, hacking in the sense of breaking computer security had already been in use as computer jargon,[12] but there was no public awareness about such activities.[13] However, the release of the film WarGames that year, featuring a computer intrusion into NORAD, raised the public belief that computer security hackers (especially teenagers) could be a threat to national security. This concern became real when, in the same year, a gang of teenage hackers in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, known as The 414s, broke into computer systems throughout the United States and Canada, including those of Los Alamos National Laboratory, Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and Security Pacific Bank.[14] The case quickly grew media attention,[14][15] and 17-year-old Neal Patrick emerged as the spokesman for the gang, including a cover story in Newsweek entitled "Beware: Hackers at play", with Patrick's photograph on the cover.[16] The Newsweek article appears to be the first use of the word hacker by the mainstream media in the pejorative sense.

Pressured by media coverage, congressman Dan Glickman called for an investigation and began work on new laws against computer hacking.[17][18] Neal Patrick testified before the U.S. House of Representatives on September 26, 1983, about the dangers of computer hacking, and six bills concerning computer crime were introduced in the House that year.[19] As a result of these laws against computer criminality, white hat, grey hat and black hat hackers try to distinguish themselves from each other, depending on the legality of their activities. These moral conflicts are expressed in The Mentor's "The Hacker Manifesto", published 1986 in Phrack.

Use of the term hacker meaning computer criminal was also advanced by the title "Stalking the Wily Hacker", an article by Clifford Stoll in the May 1988 issue of the Communications of the ACM. Later that year, the release by Robert Tappan Morris, Jr. of the so-called Morris worm provoked the popular media to spread this usage. The popularity of Stoll's book The Cuckoo's Egg, published one year later, further entrenched the term in the public's consciousness.

[edit] Programmer subculture of hackers

Main article: Hacker (programmer subculture)

In the programmer subculture of hackers, a hacker is a person who

follows a spirit of playful cleverness and loves programming. It is

found in an originally academic movement unrelated to computer security

and most visibly associated with free software and open source. It also has a hacker ethic,

based on the idea that writing software and sharing the result on a

voluntary basis is a good idea, and that information should be free, but

that it's not up to the hacker to make it free by breaking into private

computer systems. This hacker ethic was publicized and perhaps